“Both Nehru and Ambedkar, as well as their followers, believed by implication that at some point in his life, the Hindu-born renunciate Buddha had broken away from Hinduism and adopted a new religion, Buddhism. This notion is now omnipresent, and through school textbooks, most Indians have lapped this up and don’t know any better. However, numerous though they are, none of the believers in this story have ever told us at what moment in his life the Buddha broke way from Hinduism. When did he revolt against it? Very many Indians repeat the Nehruvian account, but so far, never has any of them been able to pinpoint an event in the Buddha’s life which constituted a break with Hinduism.” – Dr. Koenraad Elst

“Both Nehru and Ambedkar, as well as their followers, believed by implication that at some point in his life, the Hindu-born renunciate Buddha had broken away from Hinduism and adopted a new religion, Buddhism. This notion is now omnipresent, and through school textbooks, most Indians have lapped this up and don’t know any better. However, numerous though they are, none of the believers in this story have ever told us at what moment in his life the Buddha broke way from Hinduism. When did he revolt against it? Very many Indians repeat the Nehruvian account, but so far, never has any of them been able to pinpoint an event in the Buddha’s life which constituted a break with Hinduism.” – Dr. Koenraad Elst

When did the Buddha break away from Hinduism?

When did the Buddha break away from Hinduism?

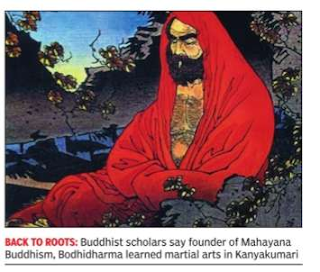

Orientalists had started treating Buddhism as a separate religion because they discovered it outside India, without any conspicuous link with India, where Buddhism was not in evidence. At first, they didn’t even know that the Buddha had been an Indian. It had at any rate gone through centuries of development unrelated to anything happening in India at the same time. Therefore, it is understandable that Buddhism was already the object of a separate discipline even before any connection with Hinduism could be made.

Buddhism in modern India

Buddhism in modern India

In India, all kinds of invention, somewhat logically connected to this status of separate religion, were then added. Especially the Ambedkarite movement, springing from the conversion of Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar in 1956, was very driven in retro-actively producing an anti-Hindu programme for the Buddha. Conversion itself, not just the embracing of a new tradition (which any Hindu is free to do, all while staying a Hindu) but the renouncing of one’s previous religion, as the Hindu-born politician Ambedkar did, is a typically Christian concept. The model event was the conversion of the Frankish king Clovis, possibly in 496, who “burned what he had worshipped and worshipped what he had burnt”. (Let it pass for now that the Christian chroniclers slandered their victims by positing a false symmetry: the Heathens hadn’t been in the business of destroying Christian symbols.) So, in his understanding of the history of Bauddha Dharma (Buddhism), Ambedkar was less than reliable, in spite of his sterling contributions regarding the history of Islam and some parts of the history of caste. But where he was a bit right and a bit mistaken, his later followers have gone all the way and made nothing but a gross caricature of history, and especially about the place of Buddhism in Hindu history.

The Ambedkarite world view has ultimately only radicalized the moderately anti-Hindu version of the reigning Nehruvians. Under Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, Buddhism was turned into the unofficial state religion of India, adopting the “lion pillar” of the Buddhist Emperor Ashoka as state symbol and putting the 24-spoked cakravarti wheel in the national flag. Essentially, Nehru’s knowledge of Indian history was limited to two spiritual figures, viz. the Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi, and three political leaders: Ashoka, Akbar and himself. The concept of cakravarti (“wheel-turner”, universal ruler) was in fact much older than Ashoka, and the 24-spoked wheel can also be read in other senses, e.g. the Sankhya philosophy’s world view with the central Purusha/Subject and the 24 elements of Prakrti/Nature. The anglicized Nehru, “India’s last Viceroy”, prided himself on his illiteracy in Hindu culture, so he didn’t know any of this, but was satisfied that these symbols could glorify Ashoka and belittle Hinduism, deemed a separate religion from which Ashoka had broken away by accepting Buddhism. More broadly, he thought that everything of value in India was a gift of Buddhism (and Islam) to the undeserving Hindus. Thus, the fabled Hindu tolerance was according to him a value borrowed from Buddhism. In reality, the Buddha had been a beneficiary of an already established Hindu tradition of pluralism. In a Muslim country, he would never have preached his doctrine in peace and comfort for 45 years, but in Hindu society, this was a matter of course. There were some attempts on his life, but they emanated not from “Hindus” but from jealous disciples within his own monastic order.

So, both Nehru and Ambedkar, as well as their followers, believed by implication that at some point in his life, the Hindu-born renunciate Buddha had broken away from Hinduism and adopted a new religion, Buddhism. This notion is now omnipresent, and through school textbooks, most Indians have lapped this up and don’t know any better. However, numerous though they are, none of the believers in this story have ever told us at what moment in his life the Buddha broke way from Hinduism. When did he revolt against it? Very many Indians repeat the Nehruvian account, but so far, never has any of them been able to pinpoint an event in the Buddha’s life which constituted a break with Hinduism.

The term “Hinduism”

The term “Hinduism”

Their first line of defence, when put on the spot, is sure to be: “Actually, Hinduism did not yet exist at the time.” So, their position really is: Hinduism did not exist yet, but somehow the Buddha broke away from it. Yeah, the secular position is that he was a miracle-worker.

Let us correct that: the word “Hinduism” did not exist yet. When Darius of the Achaemenid Persians, a near-contemporary of the Buddha, used the word “Hindu”, it was purely in a geographical sense: anyone from inside or beyond the Indus region. When the medieval Muslim invaders brought the term into India, they used it to mean: any Indian except for the Indian Muslims, Christians or Jews. It did not have a specific doctrinal content except “non-Abrahamic”, a negative definition. It meant every Indian Pagan, including the Brahmins, Buddhists (“clean-shaven Brahmins”), Jains, other ascetics, low-castes, intermediate castes, tribals, and by implication also the as yet unborn Lingayats, Sikhs, Hare Krishnas, Arya Samajis, Ramakrishnaites, secularists and others who nowadays reject the label “Hindu”. This definition was essentially also adopted by V.D. Savarkar in his book Hindutva (1923) and by the Hindu Marriage Act (1955). By this historical definition, which also has the advantages of primacy and of not being thought up by the wily Brahmins, the Buddha and all his Indian followers are unquestionably Hindus. In that sense, Savarkar was right when he called Ambedkar’s taking refuge in Buddhism “a sure jump into the Hindu fold”.

But the word “Hindu” is a favourite object of manipulation. Thus, secularists say that all kinds of groups (Dravidians, low-castes, Sikhs etc.) are “not Hindu”, yet when Hindus complain of the self-righteousness and aggression of the minorities, secularists laugh at this concern: “How can the Hindus feel threatened? They are more than 80%!” The missionaries call the tribals “not Hindus”, but when the tribals riot against the Christians who have murdered their Swami, we read about “Hindu rioters”. In the Buddha’s case, “Hindu” is often narrowed down to “Vedic” when convenient, then restored to its wider meaning when expedient.

One meaning which the word “Hindu” definitely does not have, and did not have when it was introduced, is “Vedic”. Shankara holds it against Patanjali and the Sankhya school (just like the Buddha) that they don’t bother to cite the Vedas, yet they have a place in every history of Hindu thought. Hinduism includes a lot of elements which have only a thin Vedic veneer, and numerous ones which are not Vedic at all. Scholars say that it consists of a “Great Tradition” and many “Little Traditions”, local cults allowed to subsist under the aegis of the prestigious Vedic line. However, if we want to classify the Buddha in these terms, he should rather be included in the Great Tradition.

Siddhartha Gautama the Buddha was a Kshatriya, a scion of the Solar or Ikshvaku dynasty, a descendant of Manu, a self-described reincarnation of Rama, the son of the Raja (president-for-life) of the Shakya tribe, a member of its Senate, and belonging to the Gautama gotra (roughly “clan”). Though monks are often known by their monastic name, Buddhists prefer to name the Buddha after his descent group, viz. the Shakyamuni, “renunciate of the Shakya tribe”. This tribe was as Hindu as could be, consisting according to its own belief of the progeny of the eldest children of patriarch Manu, who were repudiated at the insistence of his later, younger wife. The Buddha is not known to have rejected this name, not even at the end of his life when the Shakyas had earned the wrath of king Vidudabha of Kosala and were massacred. The doctrine that he was one in a line of incarnations which also included Rama is not a deceitful Brahmin Puranic invention but was launched by the Buddha himself, who claimed Rama as an earlier incarnation of his. The numerous scholars who like to explain every Hindu idea or custom as “borrowed from Buddhism” could well counter Ambedkar’s rejection of this “Hindu” doctrine by pointing out very aptly that it was “borrowed from Buddhism”.

Career

Career

At 29, he renounced society, but not Hinduism. Indeed, it is a typical thing among Hindus to exit from society, laying off your caste marks including your civil name. The Rigveda already describes the munis as having matted hair and going about sky-clad: such are what we now know as Naga Sadhus. Asceticism was a recognized practice in Vedic society long before the Buddha. Yajnavalkya, the Upanishadic originator of the notion of Self, renounced life in society after a successful career as court priest and an equally happy family life with two wives. By leaving his family and renouncing his future in politics, the Buddha followed an existing tradition within Hindu society. He didn’t practice Vedic rituals anymore, which is normal for a Vedic renunciate (though Zen Buddhists still recite the Heart Sutra in the Vedic fashion, ending with “sowaka”, i.e. svaha). He was a late follower of a movement very much in evidence in the Upanishads, viz. of spurning rituals (karmakanda) in favour of knowledge (jnanakanda). After he had done the Hindu thing by going to the forest, he tried several methods, including the techniques he learned from two masters and which did not fully satisfy him, — but nonetheless enough to include them in his own and the Buddhist curriculum. Among other techniques, he practised anapanasati, “attention to the breathing process”, the archetypal yoga practice popular in practically all yoga schools till today. For a while he also practised an extreme form of asceticism, still existing in the Hindu sect of Jainism. He exercised his Hindu freedom to join a sect devoted to certain techniques, and later the freedom to leave it, remaining a Hindu at every stage.

He then added a technique of his own, or at least that is what the Buddhist sources tell us, for in the paucity of reliable information, we don’t know for sure that he hadn’t learned the Vipassana (“mindfulness”) technique elsewhere. Unless evidence of the contrary comes to the surface, we assume that he invented this technique all by himself, as a Hindu is free to do. He then achieved bodhi, the “awakening”. By his own admission, he was by no means the first to do so. Instead, he had only walked the same path of other awakened beings before him.

At the bidding of the Vedic gods Brahma and Indra, he left his self-contained state of Awakening and started teaching his way to others. When he “set in motion the wheel of the Law” (dharma-cakra-pravartana, Chinese falun gong), he gave no indication whatsoever of breaking with an existing system. On the contrary, by his use of existing Vedic and Upanishadic terminology (Arya, “Vedically civilized”, Dharma), he confirmed his Vedic roots and implied that his system was a restoration of the Vedic ideal which had become degenerate. He taught his techniques and his analysis of the human condition to his disciples, promising them to achieve the same awakening if they practised these diligently.

Caste

Caste

On caste, we find him is full cooperation with existing caste society. Being an elitist, he mainly recruited among the upper castes, with over 40% Brahmins. These would later furnish all the great philosophers who made Buddhism synonymous with conceptual sophistication. Conversely, the Buddhist universities trained well-known non-Buddhist scientists such as the astronomer Aryabhata. Lest the impression be created that universities are a gift of Buddhism to India, it may be pointed out that the Buddha’s friends Bandhula and Prasenadi (and, according to a speculation, maybe the young Siddhartha himself) had studied at the university of Takshashila, clearly established before there were any Buddhists around to do so. Instead, the Buddhists greatly developed an institution which they had inherited from Hindu society.

The kings and magnates of the eastern Ganga plain treated the Buddha as one of their own (because that is what he was) and gladly patronized his fast-growing monastic order, commanding their servants and subjects to build a network of monasteries for it. He predicted the coming of a future awakened leader like himself, the Maitreya (“the one practising friendship/charity”), and specified that he would be born in a Brahmin family. When king Prasenadi discovered that his wife was not a Shakya princess but the daughter of the Shakya ruler by a maid-servant, he repudiated her and their son; but his friend the Buddha made him take them back.

Did he achieve this by saying that birth is unimportant, that “caste is bad” or that “caste doesn’t matter”, as the Ambedkarites claim? No, he reminded the king of the old view (then apparently in the process of being replaced with a stricter view) that caste was passed on exclusively in the paternal line. Among hybrids of horses and donkeys, the progeny of a horse stallion and a donkey mare whinnies, like its father, while the progeny of a donkey stallion and a horse mare brays, also like its father. So, in the oldest Upanishad, Satyakama Jabala is accepted by his Brahmins-only teacher because his father is deduced to be a Brahmin, regardless of his mother being a maid-servant. And similarly, king Prasenadi should accept his son as a Kshatriya, even though his mother was not a full-blooded Shakya Kshatriya.

When he died, the elites of eight cities made a successful bid for his ashes on the plea: “We are Kshatriyas, he was a Kshatriya, therefore we have a right to his ashes”. After almost half a century, his disciples didn’t mind being seen in public as still observing caste in a context which was par excellence Buddhist. The reason is that the Buddha in his many teachings never had told them to give up caste, e.g. to give their daughters in marriage to men of other castes. This was perfectly logical: as a man with a spiritual message, the Buddha wanted to lose as little time as possible on social matters. If satisfying your own miserable desires is difficult enough, satisfying the desire for an egalitarian society provides an endless distraction from your spiritual practice.

The Seven Rules

The Seven Rules

There never was a separate non-Hindu Buddhist society. Most Hindus worship various gods and teachers, adding and sometimes removing one or more pictures or statues to their house altar. This way, there were some lay worshippers of the Buddha, but they were not a society separate from the worshippers of other gods or awakened masters. This box-type division of society in different sects is another Christian prejudice infused into modern Hindu society by Nehruvian secularism. There were only Hindus, members of Hindu castes, some of whom had a veneration for the Buddha among others.

Buddhist buildings in India often follow the designs of Vedic habitat ecology or Vastu Shastra. Buddhist temple conventions follow an established Hindu pattern. Buddhist mantras, also outside India, follow the pattern of Vedic mantras. When Buddhism spread to China and Japan, Buddhist monks took the Vedic gods (e.g. the twelve Adityas) with them and built temples for them. In Japan, every town has a temple for the river-goddess Benzaiten, i.e. “Saraswati Devi”, the goddess Saraswati. She was not introduced there by wily Brahmins, but by Buddhists.

At the fag-end of his long life, the Buddha described the seven principles by which a society does not perish (which Sita Ram Goel has given more body in his historical novel Sapta Shila, in Hindi), and among them are included: respecting and maintaining the existing festivals, pilgrimages and rituals; and revering the holy men. These festivals, etc. were mainly “Vedic”, of course, like the pilgrimage to the Saraswati which Balaram made in the Mahabharata, or the pilgrimage to the Ganga which the elderly Pandava brothers made. Far from being a revolutionary, the Buddha emphatically outed himself as a conservative, both in social and in religious matters. He was not a rebel or a revolutionary, but wanted the existing customs to continue. The Buddha was every inch a Hindu.

» Dr. Koenraad Elst is a Belgian writer and orientalist (without institutional affiliation). He was an editor of the New Right Flemish nationalist journal Teksten: Kommentaren en Studies from 1992 to 1995, focusing on criticism of Islam. He has authored fifteen English language books on topics related to Indian politics and communalism, and is one of the few western writers (along with François Gautier) to actively defend the Hindutva ideology.

The Twenty-Two Pledges of a Neo-Buddhist

- I will not accept Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh as God and will not worship them.

- I will not accept Rama and Krishna as God and will not worship them.

- I will not accept Gauri, Ganpati, etc. belonging to Hindu canon, as God / Goddesses and will not worship them.

- I do not have any faith in divine incarnation.

- That the Buddha is the incarnation of Vishnu is a mischievous and false propaganda. I do not believe in it.

- I will not perform Shraddha Paksh or Pinda Pradaana (rituals to respect the dead).

- I will not act contrary to principles and teachings of Buddhism.

- I will not get any function performed in which the Brahmin is officiating as a priest.

- I believe that all human beings are equal.

- I will strive to establish equality.

- I will follow the Eightfold Path prescribed by the Buddha.

- I will abide by the Ten Paramitas prescribed by the Buddha.

- I will show loving kindness to all animals and look after them.

- I will not commit theft.

- I will not commit adultery.

- I will not speak lies.

- I will not indulge in liquor drinking.

- I will live my life by relating pradnya (knowledge), sheel (purity of action) and karuna (compassion).

- I renounce Hinduism which has proved detrimental to progress and prosperity of my predecessors and which has regarded human beings as unequal and despicable; and embrace Buddhism.

- I have ascertained that Buddhism is saddamma (pure way of life).

- I believe that this (embracing Buddhism) is my new birth.

- I take the Pledge that hereafter I shall live / behave as per the teaching of the Buddha.