A few weeks ago, the Saraswati River was in the news when NDTV reported, “4,500-year-old civilisation in Rajasthan has mythical Saraswati link.” The excavation uncovered a 23-metre-deep ancient river channel, potentially a paleo-channel linked to the Rig Veda’s Saraswati River. The artefacts discovered are attributed to five periods: the Post-Harappan Period, the so-called Mahabharata Period, the Maurya Period, the Kushana Period, and the Gupta Period.

Bhaskar English claimed the site was 5,500 years old. A Mauryan mother-goddess statue was dated to around 400 BCE, and a Shiva-Parvati terracotta statue was reportedly dated to ‘more than’ 1000 BCE. It was claimed that researchers found the oldest known seals bearing the Brahmi script in the Indian subcontinent, which would add a vital piece to India’s linguistic history. This news was widely reported across news channels and print media.

I recalled discussions with my friend and erstwhile colleague in the CSIR, the late Professor Kochhar, about his book The Vedic People, Their History and Geography. He describes in his book two Saraswatis: the mighty Naditama Saraswati, identified with the Helmand River in Afghanistan, and the smaller, rain-fed Vinashana Saraswati, identified with the Ghaggar in Rajasthan. In a later interview with Nithin Sundar, he elaborated on this distinction.

In earlier times, the media might have engaged with Kochhar’s theory, exploring whether the paleo-channel was the Vinashana Saraswati. Today, such discussions are rare in mainstream media. Alert reporters might have questioned the use of “Mahabharata Period” to describe the Painted Grey Ware Period or Early Iron Age in India (1200 BCE–300 BCE), as no archaeological evidence supports the occurrence of Mahabharata events. They might also have noted that a Mauryan mother-goddess statue could not date to 400 BCE, as the Maurya Kingdom was founded around 322 BCE. Similarly, identifying statues from 1000 BCE as depicting Shiva and Parvati is questionable, as the legend of this divine couple emerged later. The Rig Veda mentions Rudra but not his consort. Likewise, questions would arise about seals containing Brahmi script. What was written on those seals? How were their dates determined? How could the discovery of a few seals significantly contribute to India’s linguistic history?

As of now, no serious academic discussions have emerged on this excavation, but internet theories are circulating suggesting that the Harappan urban civilisation continued almost uninterrupted, challenging the notion of a “second urbanisation” that began in the Gangetic plains – and slowly spread across India – after the decline of the Indus Valley civilisation.

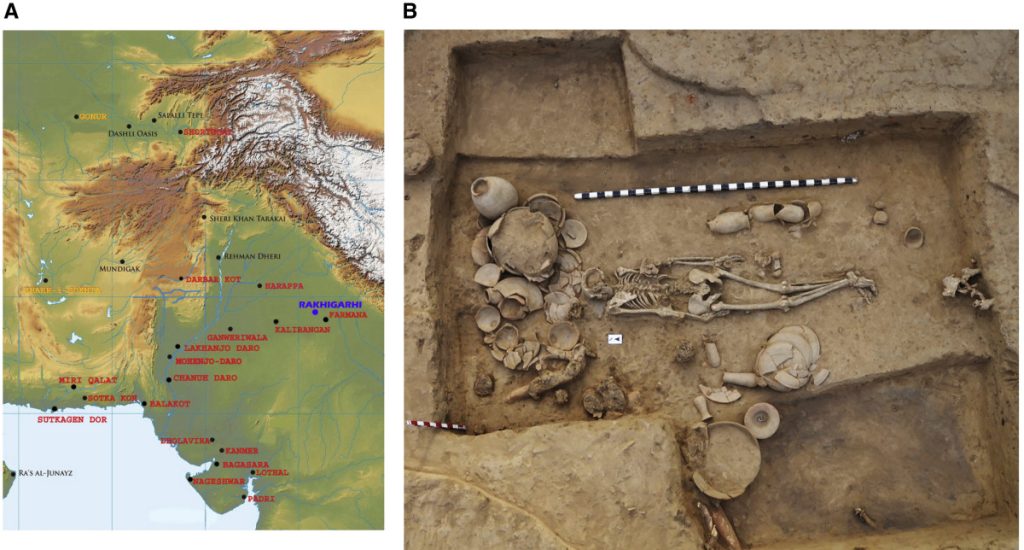

This pattern aligns with findings from Rakhigarhi. A genetic study of a single skeleton from Rakhigarhi, published in Cell (2019) by Vasant Shinde et al., was used by some reputable archaeologists to draw broad conclusions about the Harappan population and to challenge the Aryan Migration Theory (AMT).

Photograph of the I6113 burial (skeletal code RGR7.3, BR-01, HS-02) and associated typical IVC grave goods on the above-discussed paper ‘An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers’.

The study analysed the DNA from one female skeleton, revealing a mix of ancient South Asian hunter-gatherer and Iranian-related ancestry but no Steppe pastoralist ancestry. Critics, such as Tony Joseph, argued that a single sample cannot represent the genetic diversity of a civilisation spanning thousands of years and a vast geographic area.

However, these critical voices were largely overshadowed by the Hindutva narrative that resonated across India. Conveniently overlooked is that the full excavation report for Rakhigarhi, based on Amarendra Nath’s excavations between 1997 and 2000, remains unpublished; only a draft report is available. No comprehensive information exists on the ongoing excavations led by Dr. Sanjay Kumar Manjul at Rakhigarhi.

Indian archaeology suffers from several serious defects. First, excavations often fail to maintain strict stratigraphic discipline (layer-by-layer recording). Second, interpretations are frequently driven by nationalist, regional, religious, or sectarian agendas rather than objective evidence. Third, archaeological findings are often announced through press conferences before they appear in rigorous peer-reviewed journals. Finally, conclusions often involve speculative interpretive leaps.

The same is true for the Keeladi and Sivagalai findings, which raise significant questions, some of which were raised in an article in The Wire in 2019. As someone familiar with the Tamil context, I propose to raise pertinent questions that experts have failed to address.

The Tamil Nadu government and its chief minister have announced the following findings regarding Keeladi and Sivagalai:

- Keeladi represents the high point of the Sangam period.

- Keeladi unearthed Tamil Brahmi-inscribed potsherds dating to 580 BCE, which means that writing in India first began in Tamil Nadu.

- The inscribed potsherds suggest that Tamils were highly literate.

- Keeladi’s findings indicate a highly developed urban civilisation, which means that the second urban age began simultaneously in Tamil Nadu and the Gangetic plains.

- Keeladi’s findings suggest a river valley civilisation.

- Keeladi’s graffiti show similarities to signs found on Indus Valley artifacts.

- Sivagalai’s findings indicate that the Iron Age in Tamil Nadu began as early as 3345 BCE.

These conclusions will be analysed individually below:

High point of Sangam Period

The very title of the book published by the Tamil Nadu government is “Keeladi: An urban settlement of the Sangam Age on the banks of River Vaigai”.

What is the Sangam age?

In his book The Primary Classical Language of the World, Devaneya Pavanar claims Tamil began its journey 200,000 years ago and became a developed language between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago. At the other extreme, Herman Tieken, in his book Kavya in South India – Old Tamil Sangam Poetry, argues that the Sangam poems were written in the 9th or 10th century CE — just 1,000 years ago. However, the broad consensus is that the Sangam poems were composed between 100 BCE and 400 CE.

For instance, in his essay in A Concise History of South India, the scholar Noburu Karashima states, “The extant Sangam poems… are usually dated between the first and third centuries CE.” These dates are not arbitrary. The poems depict a society where Brahmins regularly chanted Vedas. For example, Madurai Kanchi, a poem describing the city of Madurai, near which Keeladi is located, states, “There are Brahmins who sing the Vedas well, following tradition with great discipline.” Karashima notes that “some Sangam kings in Tamilakam are recorded in these poems to have performed Vedic rituals by setting up yupa pillars”, indicating Aryan cultural influence by the late 1st millennium BCE, about 2,000 years ago.

Nearly all Sangam works, including the famed Tolkappiyam, mention Brahmins and the Vedas, and some reference Jain and Buddhist schools. It is evident to an impartial reader that Tamil Nadu’s historical period cannot be separated from the rest of India. For instance, Pattinappalai, a Sangam work, describes trade at the Chola port of Kaverippoompattinam: “Swift horses with lifted heads arrive on ships from abroad, sacks of black pepper arrive from inland by wagons, gold comes from northern mountains, sandalwood and akil wood come from the western mountains, and materials come from the Ganges. Pearls come from the southern ocean and coral comes from the eastern ocean. The yields of river Kāviri, things from Eezham (Sri Lanka), products made in Kāzhagam (Myanmar).”

Thus, there is a general consensus that the Tamil country was thriving at least in the early years of the Common Era. As David Shulman states in his book Tamil – A Biography, “By the first century CE, an anonymous manual for seafarers, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, gives names of major ports and cities along the South Asian coast, including sites in the far south, nearly all of which are Dravidian toponyms.”

The problem arises when Tamil’s antiquity is pushed into the centuries before the Common Era. If Keeladi indeed represents a period approximately 600 years before what is commonly known as the Sangam Age, calling it an urban settlement of the Sangam Age is ahistorical and inaccurate. But does it really represent a period 600 years before the Common Era? Let us analyse the data presented.

An image of the excavation site displayed in the Keeladi Museum website. Photo: keeladimuseum.tn.gov.in

Potsherds date to 580 BCE

How did the archaeologists of Tamil Nadu ascribe the date of 580 BCE to the potsherds found in Keeladi? They used carbon dating, but the potsherds themselves were not dated; instead, bits of charcoal from the same stratigraphic layer were analysed. Any archaeology textbook will explain that a radiocarbon laboratory can determine how long ago a tree, which later became charcoal, died. This date alone reveals little about the site. Archaeologists must carefully assess the context to determine whether artifacts in the same layer are contemporaneous with the charcoal. Routinely transferring the charcoal’s date to the artifacts, as done here, is not scientifically rigorous.

Let me quote the relevant passage from the book: “The dates of all six samples fall between the 6th century BCE and 3rd century BCE. The sample collected at the depth of 353 cm goes back to end of the 6th century BCE and another at the depth of 200 cm goes back to early 3rd century BCE. As there is a considerable deposit below the dated layer and also above the layers, the Keeladi cultural deposit could be safely dated between 6th century BCE and 1st century CE.”

In fact, the book itself notes that one charcoal sample was dated between 206 and 345 CE, contradicting the claim that “The dates of all six samples fall between the 6th century BCE and 3rd century BCE.” This inaccuracy undermines the reliability of the dating process.

The book further states:

“The total cultural deposit of this trench is 360 cm and the carbon samples were collected at the depth of 353 cm i.e. 7 cm above the natural soil. The two Tamil-Brahmi inscribed potsherds were collected at the depth of 300 cm. The thickness of the cultural deposit that exist between the spot (carbon sample) and the artefacts (Tamil-Brahmi inscribed potsherds) is about 53 cm. The time-period for the accumulation of 53 cm cultural deposit would be a century or less. This chronological frame is arrived based on other AMS dates obtained at this site. All the five carbon samples collected between 353 cm and 207 cm of the cultural deposit were dated between 580 BCE (calibrated date 680 BCE) and 190 BCE (cal. 205 BCE). Thus, the time taken for the accumulation of 150 cm cultural deposit (353-207=146cm) is about 400 years. In the sense, it took about a century or less to accumulate about 40-50 cm cultural deposit. The calibrated date obtained at the depth of 353 cm is 680 BCE and the Tamil-Brahmi inscribed potsherd collected at the depth of 300 cm could be easily dated to 6th century BCE (cal. 580 BCE).”

Notably, the charcoal sample dated to 206-345 CE is omitted here, reducing the six samples to five. To my knowledge, no method can precisely determine the time required for a cultural deposit to form. At best, archaeologists can estimate that artifacts in a layer belong to a time band. It is astonishing that the authors confidently assign the date of 580 BCE to the potsherds based on this flawed reasoning.

This approach is further highlighted in an article in Frontline by the participating archaeologist and a colleague:

“The stratigraphy of all the trenches at Keeladi from the lower level to the top level carries distinct features with the same culture. The most significant findings came from trench/quadrant YP7/4. There were three cultural layers found in this quadrant, the lowest layer being 353 cm to 200 cm below surface belonging to circa 580 BCE. The natural soil was found at 410 cm. These cultural layers are identified by archaeologists on the basis of soil deposit, soil colour, texture and the nature of the artefacts found. The middle layer being 200 cm and above was placed between the mid-third century and 1st century BCE.”

This passage implies that all artifacts in the lowest layer (353 cm to 200 cm) are dated to “circa 580 BCE.” However, the middle layer (from 200 cm upward) contains artifacts spanning the “mid-third century and 1st century BCE.” This suggests that, in one quadrant, all objects between 353 cm and 200 cm belong to a single year (580 BCE), but just above this depth, artifacts span a broader time range. This interpretation is scientifically implausible and highlights the flawed methodology.

The claim that Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions date to 580 BCE is made to assert that Tamils invented writing in India before Brahmi began to be used in the edicts of Ashoka, the Mauryan emperor of the 3rd century BCE. However, evidence from Keeladi itself tells a different story. One potsherd bears the name “Thisan”, a Prakrit name, and the grapheme (the written symbol representing a sound) for “sa” is non-Tamil, as Tamil lacks a letter for “sa”, which is the same as in Ashokan Brahmi.

Subbarayalu notes in A Concise History of South India that pottery inscriptions found in Tamil Nadu include eleven such letters derived from Prakrit or Sanskrit. This suggests that Tamils developed Tamil-Brahmi on their own, but incorporated in it letters not used in their own language for broader use. Is it plausible? It is overlooked that Tamil inscriptions before the 5th century CE, such as the Pulankurichi inscription, are primitive and often contain errors. They mostly consist of names and rarely form coherent sentences.

If the Tamils had indeed developed the Brahmi script, they did not progress beyond basic inscriptions for more than one thousand years! In contrast, others, like those who inscribed the edicts of Ashoka, made significant linguistic advancements.

The Keeladi Museum. Photo: keeladimuseum.tn.gov.in

Tamils were highly literate

The claim that pottery fragments bearing inscribed names indicate the literacy of their owners is frequently made without evidence. Inscribing names on vessels was a common practice and does not necessarily mean the owner was literate. Before the modern era, the majority of the global population was illiterate – only about 12% of people were literate in 1820 – and the Tamils were no exception. In the pre-modern era, there was generally no economic necessity for widespread literacy.

Highly developed urban civilisation

The Keeladi cultural deposits span an area of 110 acres, but only a fraction has been excavated. By comparison, the Rakhigarhi archaeological site covers approximately 865 acres. According to the Keeladi report, the site’s cultural phases are divided into Early Historic Period Phase 1 (6th century BCE to mid-3rd century BCE) and Early Historic Period Phase 2 (mid-3rd century BCE to 1st/2nd century BCE). However, the Archaeological Survey of India categorises Keeladi into three cultural periods: Pre-300 BCE, Early Historic Period (300 BCE to 300 CE), and Post-Historic Period (post-300 CE).

The report notes that artifacts from the Early Historic Period Phase 1 include fine black and red ware, black ware, and associated red-slipped ware. Structural remains, such as a terracotta ring well and a brick structure, indicate building activity during this phase. A rectangular silver punch-marked coin also dates to this period. However, the artifacts are hardly remarkable. Not one of them could confidently be said to be of Tamil origin, except perhaps the pots.

Also read: Keeladi Sparks Fresh Political Firestorm as Archaeologist Cries Foul

Notably, the brick structure uncovered is not significant enough to suggest a major construction. In his foreword, Professor Rajan remarks, “One need not depend solely on brick structures for urbanisation, as we could not come across any such massive brick structures in Tamil Nadu, even during the period of medieval dynasties such as the Pallavas, Pandyas, and Cholas. In tropical and subtropical climatic zones, wooden superstructures are favoured over brick structures. The brick structures and other artifacts unearthed at Keeladi clearly point to the existence of urbanisation.” This is a surprising claim, especially given assertions that Tamil civilisation begins where the Indus Valley civilisation ends – a civilisation renowned for its extensive use of bricks.

It defies logic to propose that a major urban civilisation existed without evidence of significant buildings, roads, or temples. Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that Tamil Nadu was technologically advanced enough during this period to support a large urban population. In the article “Archaeological Urban Attributes” from the book Eurasia at the Dawn of History: Urbanization and Social Change, the author lists 21 urban attributes to assess the level of urban development at archaeological sites. These include population, area, density, royal palaces, royal burials, large temples, craft production, markets or shops, fortifications, gates, connective infrastructure, intermediate-order temples, residences for lower elites, formal public spaces, planned epicentres, burial places for lower elites, social diversity, agriculture within the settlement, and imports.

At Keeladi, apart from abundant pottery fragments, no significant finds indicate a robust urban civilisation. The single punch-marked silver coin, possibly from the 6th century BCE, is noteworthy but inconclusive, as such coins remained in circulation for centuries – in fact as late as 3rd century AD. Thus, there is no compelling evidence to support the claim that Keeladi was part of a major urban civilisation.

River valley civilisation

Keeladi is situated on the banks of the Vaigai River, a rain-fed river spanning 258 kilometres with a drainage basin of approximately 7,000 square kilometres. In contrast, the world’s well-known river valley civilisations drain much larger areas. For instance, the Indus-Harappa civilisation covers an area of 1.25 million square kilometres, the Nile’s basin spans 2.8 million square kilometres, the Euphrates and Tigris rivers cover an area of 890,000 square kilometres, and the Yangtze covers 1.8 million square kilometres. These river valley civilisations have made spectacular and unique contributions to the world’s heritage. Keeladi has not yet provided evidence compelling enough to be recognised as a river valley civilisation.

Keeladi and Harappan Civilisation

Massive, or even compact, brick constructions are missing in Keeladi. Archaeologists in Tamil Nadu highlight the similarities between the graffiti found in Keeladi and those found at Harappan sites, and argue that there is incontrovertible proof that Keeladi is a continuation of the Harappan civilisation. Every region in India carries some imprints of the Harappan civilisation. After all, migrations must have taken place from the northwest in all directions inward. The problem arises when claims are made that the Tamils are the sole descendants of that civilisation and that their graffiti were originally inscribed at Harappan sites.

In fact, ancient graffiti are truly a global phenomenon, and scholars have long noted striking similarities in form, function, and symbolism across cultures – from early Egypt and Rome to Mesoamerica and South Asia. These commonalities reflect deeper aspects of human behaviour rather than historical diffusion alone. Yes, the Tamils must have carried the memories of their Harappan ancestors, but they were not unique.

An image displayed in the ‘Sea Trade’ page of the Keeladi Museum. Photo: keeladimuseum.tn.gov.in

Sivagalai and the Iron Age

Earlier this year, the Tamil Nadu government published a book titled Antiquity of Iron – Recent Radiometric Findings from Tamil Nadu. In that book, the chief minister of Tamil Nadu announced that “scientific dates securely place the introduction of iron in Tamil Nadu in the time bracket of 2953 BCE to 3345 BCE.”

I wrote an article for Outlook magazine in which I pointed out the flawed method of transferring the age of carbon bits to objects found nearby. In that article, I stated: A paddy sample from an urn with an intact lid was dated to 1155 BCE. In the same trench (A2), a charcoal bit found near urn 1 was tested, and its age was found to be 3259 BCE. A ceramic piece found near the same urn was tested by the OSL method, and its age was determined to be 2427 BCE.

In other words, the earliest age obtained from the tests was applied to iron objects found in the same 10-metre-by-10-metre trench. The trench was not pristine but highly disturbed. Thus, these dates are unlikely to be accepted by reputable archaeologists without rigorous analysis, especially since the implication is that the same burial site was used for 2,000 years without significant changes in the objects found.

I also cited an article in Science that quoted Professor David Killick of Arizona State University questioning the method of transferring the age of carbon bits to artifacts. Perhaps in response to my piece, Frontline published an article by the professor himself, who appeared to argue that the iron artifacts could be of the same age as the carbon bits. I immediately wrote to the professor, seeking clarification. Below is a summary of my correspondence with him, which I have shared with The Wire.

In my email dated March 1, 2025, I wrote:

“In your excellent piece in Frontline magazine, you suggest it is unlikely that three charcoal samples from three different urns could all be old charcoal. However, the charcoal bits were not found inside unbroken urns. They were collected from a highly disturbed and frequently visited burial site. All three bits were found, if I am not mistaken, within an area of 100 square metres. What is striking is that the paddy sample from a sealed urn in the same trench yields a date of 1153 BCE, but the charcoal bit found near a broken urn gives a date of 3259 BCE. Additionally, the ceramic sample from the same urn (A2, urn 1) yields a date of 2459 BCE, which is 800 years later than the carbon sample found near it.”

His response, dated March 3, 2025, was as follows:

“You appear to be mistaken in asserting that all three of the oldest charcoal dates are on loose charcoal in the soil. In fact, two of the three were found within urns (see Table 2 in the report). The difference between the two dates within urns from unit A3 (2950 ±30 BP on paddy rice from Urn-3 and 4540 ± 30 BP on charcoal from Urn-1) does not prove that the latter date is incorrect. I interpret this to mean that the cemetery was used over a very long span of time, as cemeteries often are. If there had been only one date of around 4500 BP, my alarm bells would have rung, but because this date aligns with two other very similar dates (one inside an urn, one outside), I am inclined to accept it.”

My response, dated March 15, 2025, was as follows:

“I request that you review the report again. It states: “In a few cases, the lid of the urn was found intact, which did not permit the percolation of soil inside the urn. In others, the lids were broken and collapsed, allowing soil to fill the urns… The iron objects were placed both inside and outside the urns. Inside, they were placed at the bottom of the urn.” Nowhere in the report is it explicitly stated that the charcoal was collected from within the urns. On the contrary, it explicitly mentions that the samples were collected from the trenches. If the samples had been collected from within the urns, this would have been specifically noted, as was done in the case of the paddy.”

The professor responded on April 12, 2025:

“You will need to take these questions up with the archaeologists who excavated the sites. The only point I can address is the first. The sites are cemeteries, so there is no reason to assume iron was manufactured at them. Iron slag is certainly known from Tamil Nadu, and a furnace is illustrated in the report, but to my knowledge, there are no radiocarbon dates for these yet. Again, you will have to pursue this with the archaeologists. I was simply asked to evaluate the report as written.”

I forwarded the entire correspondence to Frontline magazine, requesting a response from the archaeologists, but there has been no reply from the magazine so far.

Conclusion

I am not suggesting for a moment that the Keeladi and Sivagalai findings are unimportant. Keeladi is significant as the first non-burial site where numerous artifacts have been excavated. Similarly, Sivagalai might indicate that agriculture in Tamil Nadu began much earlier than previously thought.

However, it is unfortunate that flawed attempts to prove the antiquity of Tamil language and culture rely on methods that may not withstand scientific scrutiny. What is urgently needed is uncompromising, rigorous analysis. The same logic applies to the ongoing work at Rakhigarhi and Bahaj.

The antiquity of Indian civilisation has never been in doubt. Likewise, Tamil is already among the world’s most ancient languages, and its culture is globally renowned. They don’t need propping up with claims that may fail scientific tests. Archaeology must not become a tool for national or regional chauvinists.

P.A. Krishnan is an author in both English and Tamil. He regularly contributes to various journals and magazines.