The real position of the cradle of Indo-Europeans has been to me a fascinating enigma since I learned about this mysterious 'people', and I often dreamed about a research project on that, but never daring to propose one in a real academic context. I am an Indologist with some knowledge of historical linguistics, and Indo-European studies are for me a sort of hobby, implying sciences that I have not properly studied like archaeology, genetics, physical anthropology. Anyway, in the last days, having finally some time after conferences and applications, I have looked again at the topic, starting from a remarkable passage of an important book.

Previously in this blog, I have already cited the great work of Bernard Sergent on Indo-Europeans (Les Indo-Européens. Histoire, langues, mythes, Paris 1995), that I could buy more than two years ago in a shop of secondhand books in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, kept by Armenians. The price was not cheap, but it looked like an interesting and rich book, and now I can confirm that even more. Sometimes it is impressive how the fortuitous finding of a book can influence your future ideas and research, that is, if you are a researcher, your life itself. At p.432, in the chapter about Indo-Europeans and archaeology, it is written that the lithic assemblage of the first Kurgan culture in Ukraine (Sredni Stog II, identified with the Indo-Europeans by Gimbutas), coming from the Volga and South Urals (p.399), recalls that of the Mesolithic-Neolithic sites to the east of the Caspian sea, Damdam Chesme 2 and the cave of Dzhebel, where there are already individual burials in a flexed position and breeding of sheep and goats. Therefore, Sergent adds, the authors who have remarked this similarity have concluded that the men who settled on the Volga came from the region of Dzhebel. He writes more precisely that the people of the first Kurgan phase are ancient Mesolithic people of Dzhebel who, having learned agriculture, have brought it to the Volga. Thus, he places the roots of the Gimbutas' Kurgan cradle of Indo-Europeans in a more southern cradle. But he does not stop here. He adds that the Dzhebel material is related to a Paleolithic material of Northwestern Iran, the Zarzian culture, dated 10000-8500 BC, and in the more ancient Kebarian of the Near East. He also remarks that the mutton appears to be domesticated at Zawi Chemi Shanidar, one of the most important Zarzian sites, from 9000 BP, as it is later in Dzhebel. Then, he adds the linguistic remark that many authors consider the Indo-European language related, first of all, to the Semitic-Hamitic linguistic family, because of root structure (with 2 or 3 consonants), grammar (the fusional system instead of agglutinative), phonetics (including laryngeals), and a very important common vocabulary, especially with Semitic, for instance the number seven, and he adds that there is a rich comparative material showing that all seven first numbers are common between Indo-European and Semitic. He concludes (p.434) that more than 10000 years ago the Indo-Europeans were a small people close to Semitic-Hamitic populations of the Near East.

I had already an idea of Sergent's theory from the writings of K. Elst, nonetheless when I read it in detail in this book, I found it surprising and intriguing, and I tried to know more about Dzhebel and Damdam Chesme, but I could not find much. I did not give the due importance to the Zarzian element, actually I had a prejudice about the Zagros area, that I used to identify with the Elamite culture and language. But only a southwestern part of the Zagros mountains was part of Elam in historical times. The Zarzian sites are more to the north: Zarzi, Palegawra and Zawi Chemi Shanidar are in the Iraqi Kurdistan, to the east of Kirkuk and Erbil. In the Wikipedia description of the Zarzian culture (apparently taken from A. Burns, cp. this post), we read this sentence: "The Zarzian culture is found associated with remains of the domesticated dog and with the introduction of the bow and arrow. It seems to have extended north into the Kobistan region and into Eastern Iran as a forerunner of the Hissar and related cultures." Kobistan is more often called Gobustan, in Azerbaijan, while the Hissar culture normally indicates a Neolithic culture in northern Afghanistan and southern Tajikistan.

Doing research on Google on these topics, I have found again and again the Zagros area as the source of different cultures in areas associated with Indo-Europeans, already in the Mesolithic. In the book edited by Zvelebil Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies of Temperate Eurasia and Their Transition to Farming, we find this strong statement (p.138) by G. Matyushin:

the geometric microliths and points found in the mesolithic sites of the southern Urals are identical with the inventory of the remains found in Belt Cave, Hotu, Shanidar B, Karim Shahir, Zawi Chemi Shanidar, Jarmo and other sites in southwestern Asia - the area of the origin of domestication during the tenth to eighth millennium bc.

Now, these sites are in two areas, the South Caspian region and the northern Zagros. In the previous page, the same author writes: "Sudden ecological changes at the end of the Pleistocene led to the penetration of the southern Urals by South Caspian populations, with the result that a unique culture (Yangelskaya)... developed in the area." At p.143, he observes that "anthropological data provide further evidence for the arrival of population from the south to the Urals, in the Mesolithic." For example, a burial in Davlekanovo under a hearth containing ceramics of the Mullino II type (Neolithic) had a skeleton with clear 'mediterranoid' characteristics.

At p.124, Dolukhanov writes about the cave sites at Dam-Dam-Cheshma 1 and 2, and Dzhebel in Western Turkmenistan (east of the Caspian sea, as already said), that their Mesolithic assemblages belonged, according to Korobkova, to two kinds of industries: one related to the Belt and Hotu caves, one to the Zarzian. The Zarzian again, confirming what was said by Sergent. So, we have a route going from the northern Zagros to the South Caspian to the East Caspian to the southern Urals. A route followed by Mesolithic hunters, but in the same sites we often find later domesticated goats and sheep. And, as observed by Matyushin at p.141:

Sarianidi, at p.115 f. of the History of Civilizations of Central Asia, vol.1, remarks that the same region contained Late Mesolithic caves of hunters and gatherers and sedentary villages with an economy of production, and that the earliest Neolithic sites are not those of Turkmenistan (Jeitun culture), but of northeastern Iran close to the Caspian region, where there are also Mesolithic caves, like Dzhebel and Damdam Cheshme, used as shelters by hunters even in the Early Mesolithic period (10th to 7th mill. BC). In the Dzhebel cave and Damdam Cheshme 2 domesticated animals, however, appear comparatively late, in upper Neolithic strata, suggesting that they arrived there in a fully domesticated form. And although wild sheep and goats roamed in the area, the domesticated varieties appear to have descended not from the local strains, but from those of western Asia.

At p.124, Dolukhanov writes about the cave sites at Dam-Dam-Cheshma 1 and 2, and Dzhebel in Western Turkmenistan (east of the Caspian sea, as already said), that their Mesolithic assemblages belonged, according to Korobkova, to two kinds of industries: one related to the Belt and Hotu caves, one to the Zarzian. The Zarzian again, confirming what was said by Sergent. So, we have a route going from the northern Zagros to the South Caspian to the East Caspian to the southern Urals. A route followed by Mesolithic hunters, but in the same sites we often find later domesticated goats and sheep. And, as observed by Matyushin at p.141:

Taking into account that wild sheep are absent from the Urals and the surrounding areas, and that their region of origin was northern Mesopotamia and northern Iran, it can be assumed that stockbreeding was introduced to the Urals from Iran and the southern shores of the Caspian. The introduction of the 'southern' stockbreeding elements may date well back into the Mesolithic, possibly to the date of the appearance of the geometric microliths (ninth to seventh millennia bc).However, according to the table that he gives at p.143, ovicaprids are attested in South Urals only a short time before 6000 BC.

Sarianidi, at p.115 f. of the History of Civilizations of Central Asia, vol.1, remarks that the same region contained Late Mesolithic caves of hunters and gatherers and sedentary villages with an economy of production, and that the earliest Neolithic sites are not those of Turkmenistan (Jeitun culture), but of northeastern Iran close to the Caspian region, where there are also Mesolithic caves, like Dzhebel and Damdam Cheshme, used as shelters by hunters even in the Early Mesolithic period (10th to 7th mill. BC). In the Dzhebel cave and Damdam Cheshme 2 domesticated animals, however, appear comparatively late, in upper Neolithic strata, suggesting that they arrived there in a fully domesticated form. And although wild sheep and goats roamed in the area, the domesticated varieties appear to have descended not from the local strains, but from those of western Asia.

|

| Damdam Cheshme cave |

The southern Urals where the Zarzian people apparently arrived through the Caspian region are close to the area of the Samara culture on the Volga of the late 6th-early 5th millennium BC, regarded as the origin of the Kurgan Indo-European cultures. About the Neolithic period in the southern Urals, in Prehistoric Russia, p.130, it is written:

At p.142, about the Yamnaya stock-breeding:Some scholars (N.Ia. Merpert) suggest that the Yamnaya culture emanated from the south of Soviet Central Asia; graves of Zaman Baba I, Djebel, etc. have been mentioned. The influence emanating from the Kelteminar culture had evidently reached the South Ural culture (Cherbakul II) of the Middle Neolithic. The tribes who lived in the area bordering on the Urals to the west, the presumed ancestors of the Yamnaya people, were most probably influenced as well.

Stock-breeding was not an invention of the Yamnaya people. They may have learnt it from the west Siberian tribes, their eastern neighbours, and, if so, it was of Central-Asiatic, Iranian derivation.And about the "Central Asiatic centre of early agriculturalists":

only very late in its development did it influence the neighbouring Mesolithic tribes in the country further North. The earliest of the latter peoples to learn about pottery were the men of the Kelteminar culture, which was formed about the beginning of the third millennium. A pottery closely related and presumably taken over from the Kelteminar culture, appeared soon in the region of the south Urals, further North in the Gorbunovo culture, and also in the Kama and Kazan cultures west of the Urals. All these cultures belonged to a wider Ural/West-Siberian Kulturkreis. The Kelteminar pottery, which seems to be the earliest, was probably adopted from the Anau or Namazga cultures of the southern part of Soviet Central Asia.

The Neolithic Kelteminar culture, dated 5500-3500 BC, spread from northern Turkmenistan to Kazakhstan. Its stone industry had common elements with the Caspian, Ferghana and Hissar cultures (see here and here). It is remarkable that all these areas, when they first appear in history, belong to Iranian cultures. According to the Wikipedia entry, the Kelteminar people were Mesolithic groups coming from the Hissar area (South Tajikistan/North Afghanistan), with bow, arrow and dog. And we have already seen how the Hissar culture has been derived from the Zarzian.

But there is another route from the Zagros through the Caspian. Sarianidi speaks at p.124 of the Mesolithic strata of the 9th millennium BC at Kara-Kamar in northern Afghanistan and adds: "It has been suggested that like the Ghar-i Kamarband [Belt cave] and Hotu caves, Kara-Kamar reflects the spread of Mesolithic people from the Zagros mountains to the northern foothills of the Hindu Kush via the Caspian coast." And the route could go further east. In The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory : Why did Foragers become Farmers? by G. Barker, although the thesis is that at Mehrgarh in Baluchistan agriculture starts indipendently from South-West Asia, it is observed at p.162 that in Neolithic Mehrgarh the technology "included geometric microliths such as those used by the late Pleistocene and early Holocene foragers of the Zagros and Turkmenistan." J.F. Jarrige and M. Lechevallier, in an article in French of 1980, Les fouilles de Mehrgarh, Pakistan : problèmes chronologiques, observe that the trapezoidal microliths of Neolithic Mehrgarh are characteristic of the Mesolithic sites from the Kizil Kum, near the Caspian sea, to the left bank of the Amu Darya in Afghanistan.

But leaving aside the remnants of the Mesolithic period, also the new Neolithic elements point to an origin from the Zagros. In a very recent paper, The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia by K. Gangal, G.R. Sarson and A. Shukurov, we read:

Neolithic domesticated crops in Mehrgarh include more than 90% barley and a small amount of wheat. There is good evidence for the local domestication of barley and the zebu cattle at Mehrgarh [19], [20], but the wheat varieties are suggested to be of Near-Eastern origin, as the modern distribution of wild varieties of wheat is limited to Northern Levant and Southern Turkey[21]. A detailed satellite map study of a few archaeological sites in the Baluchistan and Khybar Pakhtunkhwa regions also suggests similarities in early phases of farming with sites in Western Asia [22]. Pottery prepared by sequential slab construction, circular fire pits filled with burnt pebbles, and large granaries are common to both Mehrgarh and many Mesopotamian sites [23]. The postures of the skeletal remains in graves at Mehrgarh bear strong resemblance to those at Ali Kosh in the Zagros Mountains of southern Iran [19]. Clay figurines found in Mehrgarh resemble those discovered at Zaghe on the Qazvin plain south of the Elburz range in Iran (the 7th millennium BCE) and Jeitun in Turkmenistan (the 6th millennium BCE) [24]. Strong arguments have been made for the Near-Eastern origin of some domesticated plants and herd animals at Jeitun in Turkmenistan (pp. 225–227 in [25]).

J.F. Jarrige, in an article in Pragdhara 18, of 2006, Mehrgarh Neolithic, p.151, speaks of similarities of Mehrgarh with the early Neolithic settlements "in the hilly regions forming the eastern border of Mesopotamia." These 'hilly regions' are the Zagros:

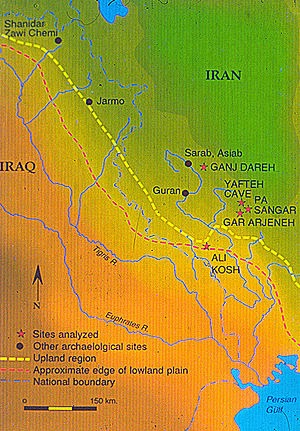

The circular houses of the earliest Neolithic villages have not been found at Mehrgarh. But quadrangular houses built with about 60 cm long narrow bricks with a herringbone pattern of impressions of thumbs to provide a keying for the mud-mortar, have been uncovered at several aceramic Neolithic sites in the Zagros, such as Ganj Dareh or Ali Kosh in the Deh Luran region of Iran, where, like at Mehrgarh, traces of red paint have also been noticed on the walls.

These are very close similarities. The circular houses are the so-called Pre-Pottery (or Aceramic) Neolithic (PPN) A of the Levant and Anatolia, the quadrangular houses the PPN B: it seems that the PPNB people of the Zagros moved directly to Mehrgarh.

As to the burials, already in the French article already cited Jarrige and Lechevallier observed in Ali Kosh and Mehrgarh a similar flexed position of the skeletons, coated with ochre, along with baskets coated with bitumen. In the Pragdhara article, he adds also "oblong-shaped cakes of red-ochre". Moreover, common gravegoods are seashells, turquoise (which was mined in Khorasan, in NE Iran, and also in Kerman, in SE Iran, see here), and even copper beads. This detail of copper already in the Neolithic levels belonging to an age of the 8th-7th mill. BC is remarkable, because it shows that the Indo-European term for copper or generally metal (ayas in Sanskrit, aiiah in Avestan, aes in Latin, aiz in Gothic) could be developed already in such an old Neolithic period (see also here about the presence of copper in Mesopotamia around 8700 BC).

Moreover, in Mehrgarh as well as in Ali Kosh and Ganj Dareh, the skeletons of children are the most richly adorned. In Sang-e Chakhmaq, in Northern Iran (south of the Alborz mountains), a site recently investigated again, a 10 month fetus was buried with 183 shell beads and 90 clay beads in the West Tappeh, dated from the end of the 8th to the early 7th mill. BC. Also there, the bodies were lying in a contracted position on the side, a burial form that according to a paper presented this year, is found in other Iranian sites like Sialk, Tepe Hissar, Shah Tepe, and Shar-i Sokhta. Thus, already in the earliest Neolithic, we find a common culture from the Zagros to northern Iran to Baluchistan. J.F. Jarrige speaks of "a sort of cultural continuum", and Catherine Jarrige, in The figurines of the first farmers at Mehrgarh and their offshoots (also in Pragdhara 18), writes about the clay figurines:

the early figurines of Mehrgarh are an essential component in the vast geographical zone which extends from Central Asia to the Zagros, whose ramifications will reach even further during the 2nd millennium. [...] These symbols circulate through the same exchange networks as raw materials, technology and funerary pratices and reveal the links, the contacts and the exchanges which occur between the different regions bounded by the Zagros flanks, Baluchistan and the Indus, the Kara Kum desert and the Makran coast.

Also the paper on Sang-e Chakhmaq compares the figurines found there to those of Jarmo in the Zagros.

The next step is agriculture. In a 2013 paper Riehl from the University of Tübingen (see also here) analyzes a Neolithic site of the Zagros, Chogha Golan, and finds there proofs of a progressive domestication of emmer from 9800 BP; moreover, there were wild barley, different wheat species, lentils and peas. So, all the elements for developing a the farming lifestyle were present, including goats (Ganj Dareh on the Zagros is one of the first sites for domesticated goats, 10000 yr BP, see here), and most of the same elements are found in Neolithic Mehrgarh and other contemporary sites in Iran: emmer and other wheat species, barley, goats.

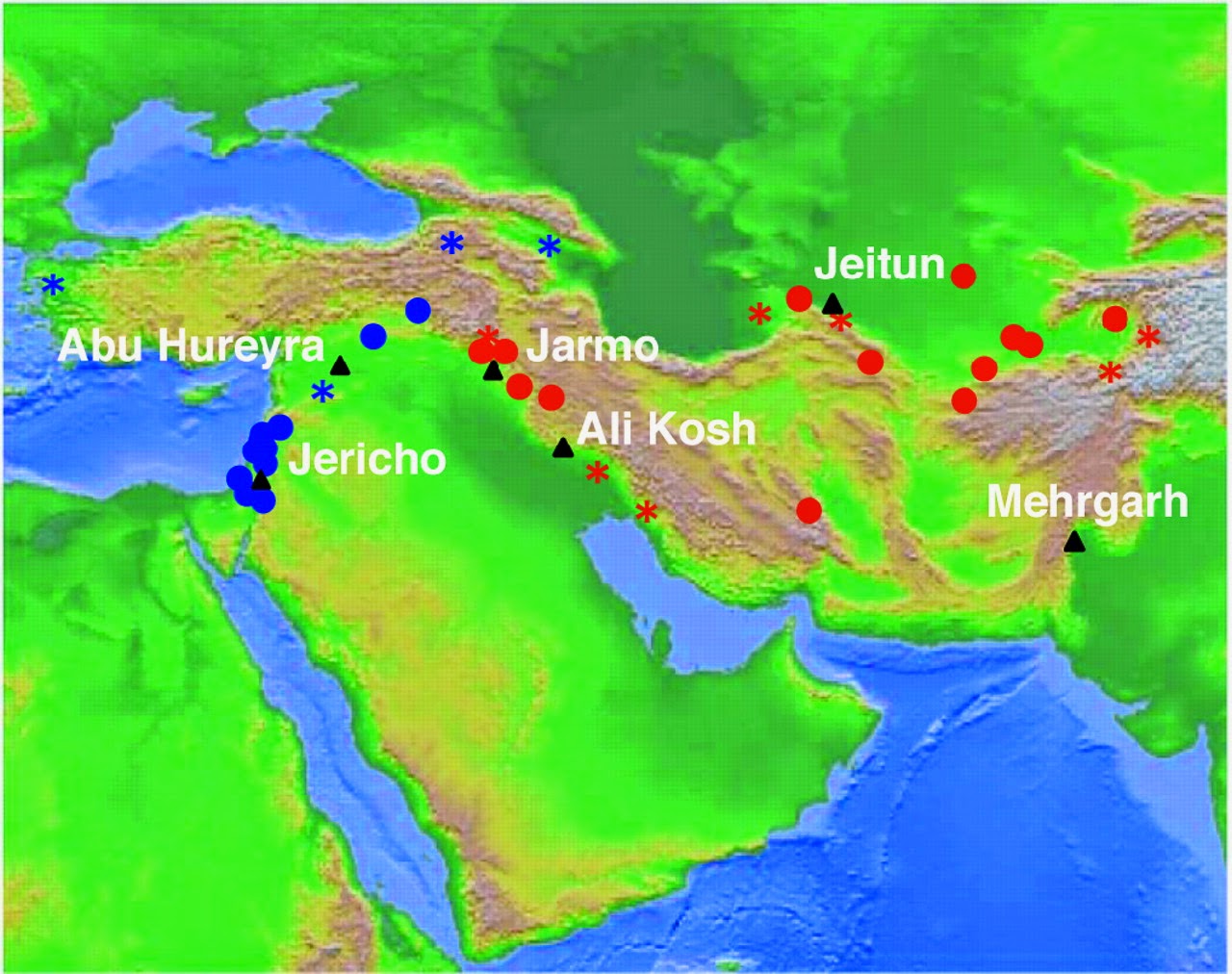

About barley, there is a map to show:

The blue dots and asterisks are the places with wild barley belonging to the 'western cluster', the red dots and asterisks are those with wild barley of the 'eastern cluster'. The triangles with the names are the Neolithic sites with domesticated barley. As we can see, the barley of the eastern type is found in the Iranian area. The difference is due to the Zagros mountains but probably also to the diffusion of a different domesticated barley, because often wild barley derives from cultivated barley. As the authors (Morell and Clegg) of the paper write:

Geographic patterns of genetic differentiation are associated with the major topographic feature within the range of wild barley, namely the Zagros Mountains (Fig. 1), that trend northwest to southeast and roughly bisect the range of the species. The Zagros also delineate the eastern edge of the Fertile Crescent; thus, the most dramatic differences in haplotype composition in wild barley occur between the Fertile Crescent and the portion of the range east of the Zagros (17). Differences in haplotype frequencies among regions also suggest that human activity, including transportation of cultivated barley among regions, has not homogenized genetic diversity across the range of the wild progenitor.And there is also a map of cultivated barley races:

Here we see how the cultivated barley of Iran belongs to the eastern type, especially in the Zagros, and also in the Indian region it is mainly of the eastern cluster. As the authors say "Accessions from the Zagros Mountains and Caspian Sea region show the lowest probability of origin in the Fertile Crescent (Fig. 2 and SI Fig. 5)." And the conclusion is that the Zagros can be the origin of the eastern domesticated barley:

The relatively broad, species-wide sample mesh in the present study suggests an origin of eastern landraces in the western foothills of the Zagros or points farther east. Much of the region immediately east of the Zagros is a high-elevation plateau, where both wild barley populations (4) and known human Neolithic sites are relatively rare (5). However, the locations of early Neolithic agropastoral settlements suggest three general regions in which the secondary domestication could have taken place. In the foothills of the Zagros, at such sites as Ali Kosh and Jarmo (Fig. 1), domesticated barley is dated to ≈7,000–8,000 cal. B.C. Domesticated barley is found at the Indus Valley site of Mehrgarh (in present day Pakistan) from ≈7,000 cal. B.C. Finally, in the piedmont zone between the Kopet Dag mountain range and Kara Kum Desert (east of the Caspian Sea in present day Turkmenistan), cultivated barley was present by ≈6,000 cal. B.C.

We can add that Fuller, in a paper on Sang-e Chakhmaq (see above), which is more ancient than the Kopet Dag sites and probably a source of them, remarks that there is no evidence there for local domestication although there is also wild barley. But there is more. In a 2008 paper by Huw Jones et al. we read:

The foothills of the Zagros Mountains are among the 3 general regions suggested as centers for a secondary domestication of barley (Morrell and Clegg 2007). One of the 2 wild barleys that our analysis suggests as likely progenitors of the nonresponsive cultivated barleys was sampled in this region (HOR 2882, 32°33′N, 48°33′E). The second of these accessions originates in the north of the Zagros Range (HOR 2680 36°30′N, 48°42′E).