There are many stories about the origin of Bengaluru’s name. One popular apocryphal version recounts the tale of a king from the Hoysala dynasty coming to the city in the 12th century on a hunting spree and losing his way. The hungry king, the story goes, was given a traditional welcome by an old woman, who offered him water and boiled beans—benda kaalu in Kannada. The grateful king was supposed to have named the settlement “Bendakaaluru”: The town of boiled beans. This evidently metamorphosed to Bengaluru in due course of time.

However, the recent discovery of a ninth century temple inscription—referring to the name of Bengaluru—has put paid to the story and, literally, relegated it to an urban legend.

There is no such doubt regarding the role played by the Kempe Gowda bloodline—the feudatory rulers under the Vijayanagara empire—who founded the city of Bengaluru. Named after their family deity’s consort, Kempamma, Kempe Gowda I founded the city in 1537. He soon constructed a mud fort with a protective moat, and established markets in its premises.

A statue of Kempe Gowda I. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A statue of Kempe Gowda I. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Kempe Gowde I is also credited with the construction of several lakes or keres in and around this original mud fort, for the purposes of drinking water and irrigation: the Dharmambudhi lake, the dried bed of which today houses Kempegowda Bus Station, and the now decrepit Kempambudhi lake are some of the most noteworthy ones. His grandson, Kempe Gowda II, also built many lakes and watchtowers around the city.

Many of these medieval lakes that once slaked the city’s thirst and watered its crops have today been ravaged by urbanization and the ensuing encroachment. Kempe Gowde I also championed the construction of several temples around the town; one of the earliest such temples that was renovated and constructed outside the fort’s perimeter was the Gavi Gangadhareshwara temple.

A view of the Gavi Gangadhareshwara temple from its front entrance. Photo courtesy Vyasa Shastry

A view of the Gavi Gangadhareshwara temple from its front entrance. Photo courtesy Vyasa Shastry

And it was to this temple that I boarded the No. 35 bus on 14 January. The time was 3.10pm and the bus was uncommonly crowded. On most days, buses starting from the Kempegowda Bus Station tend to be crowded. Bengauluru is a city in the throes of agonizing urbanization. Everything is crowded.

But this was a Saturday. And yet, the bus thronged with people. All of them, like me, were on their way to the bus stop near the swimming pool in Gavipuram. We were going to witness a breathtaking celestial phenomenon.

Opening scenes

To visit the Gavi Gangadhareshwara temple, alight at the bus stop overlooking Kempambudhi Lake. A short walk up the road leading south takes you to the temple.

Various architectural views of the temple. Photo courtesy Nagraj Vastarey

Various architectural views of the temple. Photo courtesy Nagraj Vastarey

From outside its walls the temple looks unremarkable. But on stepping into the forecourt several distinctive features catch the eye. The main idol of the temple is inside a cave that devotees descend into via steps. Unusually for a South Indian temple the complex is not aligned to any of the cardinal directions—it faces south-west. This is perhaps the first clue to the temple’s astrophysical relevance, and why it is such a draw for the hundreds of devotees who throng around me. There are more clues.

In the forecourt stand two monolithic structures, named Suryapana and Chandrapana—each consisting of a massive disc atop a supporting pillar, like giant stone lollipops. Engravings of sitting bulls on the discs face each other. The discs are identical in size and have a diameter of about 6ft. Grooves cut into the discs at right angles to each other, on both faces, giving them the appearance of a sniper rifle’s crosshairs.

Along with these structures are the objects associated with the iconography of Shiva—the trishula (trident) and the damaru (an hourglass-shaped, two-headed drum). In between the two discs there is a brass dhwajasthambha (flagstaff), and a small cubicle housing a statue of Nandi, Shiva’s bull mount.

The outer mantapa (vestibule) leading to the cave has pillars in the Vijayanagara style, set into the floor, a few inches below the level of the forecourt. The entrance to the cave is flanked by statues of Shiva’s dwarapalakas (doorkeepers).

A small flight of stairs leads one down to the cave that is hardly 6ft high; the height tapers off further into the shrine. In the cave temple the presiding idol, a Shiva linga, is surrounded by several smaller deities and sages, and the two pradakshine (circumambulatory) paths. Another statue of Nandi faces his master. There are also entrances into two secret tunnels which, according to legend, lead to Shivaganga and Varanasi.

The low height of the pradakshine paths lends itself to the Hindu customary practice of bowing one’s head while paying obeisance to god or one’s elders. A steady, thin stream of water always flows through the cave, next to the main idol. This undoubtedly harkens back to the myth of Ganga (the personification of the holy river) getting entrapped in Shiva’s hair and emerging from his matted locks as a small stream and thence flowing onto the earth.

Hence, the temple derives its name from this combination of topographical features and mythology: gavi, meaning cave, and a representation of Shiva as Gangadhareshwara (dhara meaning adorning and eshwara meaning divinity). Thus, Gavi Gangadhareswara means the Cave of the Lord who adorns the Ganga. The name of the locality, Gavipuram (puram meaning dwelling or settlement), too draws its name from the cave temple.

A touch of the sun

I was here, along with hundreds of others, on the auspicious occasion of Makara Sankranti, which marks the entry of the sun into the zodiac sign of Capricorn. Each year on this day the temple experiences a huge influx of devotees, eager to witness the headlining celestial event. Anticipation builds up to a fever pitch. In large tents specially put up to house visitors, hundreds of eyes eagerly watch TV monitors broadcasting live pictures from inside the cave. Elsewhere all over Bengaluru, thousands more wait anxiously as they watch live TV broadcasts.

Then, not a minute too soon, the rays of the descending sun made their way through an arch on the temple’s western compound wall. The rays passed through a couple of windows into the cave and pierced through the haze of the aarathi.

The beams gradually traversed the length of the Nandi’s body in the direction of his head; and then an hour before sunset, amid the beating of drums, fervent chanting and the pouring of milk libations over the idol, the rays passed through Nandi’s horns and sought the foot of the idol at precisely 5.19pm.

In ten minutes the beams enveloped the idol. Bathed in light, it shone for five whole minutes. Devotees watched their eyes glued to the screen. And then the beams moved away. This annual, ephemeral phenomenon is called Surya Majjana, or the Sun Bath.

For some devout Hindus—apart from being a visual spectacle—this phenomenon is steeped in strong religious symbolism, which explains its draw. But behind it lies a tale of scientific knowledge, architectural prowess and some intriguing local history.

The wobbling earth

As I had described in an earlier Mint on Sunday article, a unique and crucial characteristic of the earth is the tilt of its axis with its orbital plane. In the absence of this tilt (nearly 23.5 degrees in the present day), the sun would rise and set in the same position every day. And we would have no seasons at all. It this tilt that gives the planet its seasons and a temple in Bengaluru its annual celestial spectacle.

Because the earth rests on its side, so to speak, the points of sunrise and sunset move like a pendulum between the tropics, from one extreme in late December to the other in late June. Correspondingly, the length of the day varies across the world based on the sun’s real-time position.

However, on any given day, somewhere on the planet, the sun is directly overhead at noon. An object on that latitude would have its shadow move exactly on that imaginary latitudinal line from sunrise to sunset; what is more—at local noon, the object could cast no shadow at all. Think of an actor standing on a stage as a spotlight passes directly overhead, in a straight line from one side to the other, pointing straight down.

Now at each hemisphere’s summer solstice, the sun is directly overhead at the respective extreme tropical latitude (~21 June in the northern Tropic of Cancer and ~22 December in the southern Tropic of Capricorn). These are the extremes of the pendulum motion we spoke about before. The sun will go so far and no further to the north or the south. If you live outside these extremes you will never experience the sun directly overhead.

For a person located between the tropics, on the other hand, the sun is overhead at noon twice a year—once when it moves from north to south and once when it goes in the opposite direction. On the tropics, where the sun takes a U-turn so to speak, it happens only once—at the respective solstice. And outside this band, never. This is why "tropical" is a term used to describe places that are very warm at least part of the year.

Cultures all over the world have used observations of winter solstice to keep track of food reserves and agriculture. Many of them even built structures to track this southern extreme point of the sun’s perambulation. The most famous examples include ancient observatories at Stonehenge, Goseck and Chankillo, graves at Newgrange and Maeshowe, the Mayan structures at Tulum and Chichen Itza, and the Karnak Temple complex in Egypt.

Many Hindus believe that different times of the year are suitable for different types of religious worship; auspicious rituals (shubha karya), such as sacred thread ceremonies, are performed by some only during uttarayana (uttara meaning north and ayana meaning motion). Uttarayana (referring to the period of movement of the sun in the northward direction), with its longer, warmer days, signifies a period of positivity for them.

In a similar vein, many believe that dakshinayana (due to shorter periods of daylight) is associated with negative acts. Hence, penitential activities like fasts, fire sacrifices, pilgrimages and charity are undertaken by some during the sun’s movement southwards. The journey of the sun, as it seeks god and cleanses itself after witnessing the debilitating effects of dakshinayana (dakshina meaning south), is a story of redemption strikingly reminiscent of traditional customs.

Signs of confusion

The festival of Makara Sankranti marks the entry of the sun into the zodiac sign of Makara, or Capricorn. The festival is known by many other names—Pongal, Bihu, Maghi, Maghe Sankranti—in different parts of India and Nepal, and all celebrations include some form of a ritual feast, celebrating the harvest and ceremonially using new items, all signifying new beginnings. At the Gavi Gangadhareshwara temple in Bengaluru, too, this alignment of stars is known as both Makara Sankranti and uttarayana.

This year, Makara Sankranti was celebrated on 14 January. Like the dates of the solstice, it can vary by a day or so in the short term due to Earth’s period of revolution. So currently we live at a time when Sankranti falls on 14 or 15 of January.

But hang on, isn’t there something amiss here?

Recall, uttarayana is the movement of the sun in the northward direction; by definition, shouldn’t it be at the winter solstice, where the sun has reached its apparent southernmost extent? The transition to the northward movement should happen at the end of December, as discussed earlier.

By the middle of January, when the sun moves into Capricorn and Makara Sankranti is celebrated, isn’t the sun in uttarayana already? If so then why is Makara Sankranti confused for uttarayana in the temple’s ceremonies and lore? In fact, there is one more name for the Sankranti festival that I deliberately withheld earlier—it is called Uttarayan in Gujarat and parts of Rajasthan, which lends its name to the kite festival during its celebration.

Over the long term (~25,700 years), the earth wobbles around its axis, slowly changing its orientation (like a wobbly top). This phenomenon is called precession. It causes a gradual shifting of pole stars once every thousands of years.

Similarly, the date of “entry” of the sun entering different zodiac signs also varies—going through a full circle every ~25,700 years, or by 1 degree every ~71.6 years. Makara Sankranti will shift further away from the winter solstice by a day every ~72 years. Amazingly, after about 12,000 years, Makara Sankranti would happen in June, in the peak of northern hemisphere summer, and then move into the dakshinayanarealm!

There are other places also where this confusion manifests. The Tropic of Capricorn owes its etymology to the sun entering the constellation of Capricorn (Makara) at the same time of the winter solstice, about 1,700 years ago—also the time when the date of Makara Sankranti exactly matched with that of the winter solstice.

This confusion is quite puzzling given the fact that Indian astronomers were aware of this phenomenon (called ayanamsha) and computed accurate values. The Wikipedia page for Uttarayana notes that lack of understanding of differences between two different existing scales of measurement of a year causes this confusion

In 2006, a scientist in Bengaluru decided to investigate the matter further.

Structural learnings

Some two decades ago one of her colleagues showed B.S. Shylaja a photograph of the beams of sunlight falling on the Gavi Gangadhareshwara idol. Shylaja, a widely published astrophysicist and director of the Jawaharlal Nehru Planetarium in Bengaluru, was intrigued. So she paid a visit to the temple.

“I found it peculiar that it was not aligned to any of the cardinal directions. The various structures in the patio also added to my curiosity. In order to get to the bottom of it, I started visiting the temple frequently and observing shadows through the year,” she said. Many years later, realizing that this called for proper investigation, she roped in two graduate student then associated with the planetarium’s Research Education Advancement Program.

From 2006 to 2008, Jayanth Vyasanakere, who now has a doctorate in physics, and K. Sudheesh diligently observed and recorded the sun’s shadows at the temple and how these shadows fell on idols and other statuary. Over the course of their investigation, Shylaja and her team discovered that the shadow of the western pillar would fall exactly on the eastern pillar on the summer solstice sunset in late June; and, despite the trees hampering observations during sunrise, they conjectured that the shadow of the eastern pillar would fall on the western pillar at sunrise on the winter solstice.

The dhwajasthambha’s shadow falling on the eastern disc close to the summer solstice sunset. Photo courtesy Jayant Vyasanakere and B.S. Shylaja.

The dhwajasthambha’s shadow falling on the eastern disc close to the summer solstice sunset. Photo courtesy Jayant Vyasanakere and B.S. Shylaja.

Furthermore Shylaja’s team discovered that, close to the time of the summer solstice sunset, the shadow of the dhwajasthambha in the forecourt also fell on the vertical mark of the eastern "crosshairs" disc. These observations had never been made before, leading the researchers to believe that there was much more to the temple’s layout and design than merely the Makara Sankranti spectacle.

But the primary question on Shylaja’s mind remained. Why did the temple seem to celebrate Makara Sankranti and uttarayana at the same time when clearly there was a significant gap in the occurrences of both events? And if the Surya Majjana was not timed to occur at the solstice then that meant that the alignment of the idol with the sunbeams should happen not just once in the year but twice—once just before the solstice and once again when the sun took the solstice U-turn and came back. But there was no record of a second such event at the temple.

By a quirk of fate, Shylaja found a clue to resolving these problems right at home.

Art imitates life

“My father, the late Ba Na Sundara Rao, authored a book on Bengaluru’s history many years ago. I remember him showing me paintings of a barren Lalbagh. Unfortunately, he could not get the requisite permissions to feature them in his book, but through him I was aware of Thomas Daniell’s work,” she said, pointing me in the direction of the famous English landscape painter.

Daniell was a man of serious painting pedigree. Unable to establish himself as a painter of repute in England, he obtained permission to travel east in 1784—from the East India Company. On his travel to India via China, he took an assistant—his nephew, William Daniell. The Daniells spent nearly nine years (from 1786) travelling the country, making sketches, drawings and aquatints of scenery and architecture. Between 1795 and 1808, they produced Oriental Scenery—a publication of six volumes containing a total of 144 hand-coloured aquatint views of India. Two such aquatints were connected to the temple.

The first one was of the view of a nearby hill (called the Harihara gudda), just east of the temple. From the painting, it can be observed that the region surrounding the temple which had a Kempegowda tower and other upright structures was barren, and devoid of any vegetation, unlike today; it must have been ideal for making astronomical observations of the solstice.

Today, the same view is marred by thick foliage--the white paint of the Kempegowda tower (circled in orange in the picture above) barely sneaking a peek amidst the greenery.

The second aquatint—titled Entrance to a Hindoo Temple—is the mother lode. Due to the settlements next to the temple, obtaining such a vantage point is impossible today.

The footnote accompanying the painting notes the various features of the temple:

“The entrance of the temple has a very striking effect from the size and singularity of the mythological structure wrought in stone, ... trident of Mahadeva and the chakra of Vishnoo supported perpendicularly ... The passage leading to the interior which is partly evacuated, is completely choked up with large stones so as to be inaccessible. This place having now no establishment for religious duty, is accordingly deserted.”

It must be noted that the painting was from 1792—the time immediately following the Third Anglo-Mysore war. Since the temple was located outside the ramparts of the Bengaluru Fort, it must have been deserted fearing an attack, with the entrance being made inaccessible.

Nevertheless, the resemblance to the temple’s features is striking. The hill in the background contains some of the stone structures from the previous aquatint—the Kempegowda monument, a pillar and a disc atop a column. Crucially, clues regarding the temple’s architecture at the time can be garnered by careful observation. Shylaja’s team pounced on them.

The temple’s terrace was not accessible at the time Daniell produced the aquatint; the gopurams (ceremonial towers) were much closer to the entrance of the temple, which indicates that the temple has undergone a recent facelift. At some point in the past 225 years, new walls and enclosures were constructed; the three arch-like structures are now enclosed inside the temple; and, most importantly, there was no longer a window on the western wall of the temple (present location is circled in orange).

Hence the Suryapana and Chandrapana might have been used in order to ascertain the day of the solstices.

In light of this newfound evidence, Shylaja and her team concluded that the outer mantapa—with its pillars—was a later addition. The last set of the pillars in the mantapa were at the entrance of the cave; their deductions showed that the construction of the westernmost pillar (now fused with the entrance of the cave) blocked the sun’s rays from ever reaching the idol from the winter solstice onwards. It was a clever bit of architectural retrofitting, sometime in the last two centuries, that facilitated the spectacular events of January.

Taking inspiration from Shyalaja, I did some small-time sleuthing of my own. It turns out that there was another artist, James Hunter, who sketched scenes from everyday and military life in late 18th century India. He was a lieutenant in the Royal Artillery who served in the Third Anglo-Mysore war and, additionally, was a military artist—not quite boasting the same artistic credentials of the Daniells.

He too, painted the scenery of the temple, but wrongly identified it as a Moorish Mosque. In spite of it also being painted from a similar perspective, the orientation of various structures have been misrepresented. Additionally, his aquatint has one crucial extra detail—that of the arch on western compound wall, suggesting that it might have existed around 1792.

A second glance

“There is another reason I was interested in this temple. When I first heard about the event, I wondered why it had to occur only on 14 January; it was a solar event after all,” Shylaja said, adding a new twist to the tale of the temple.

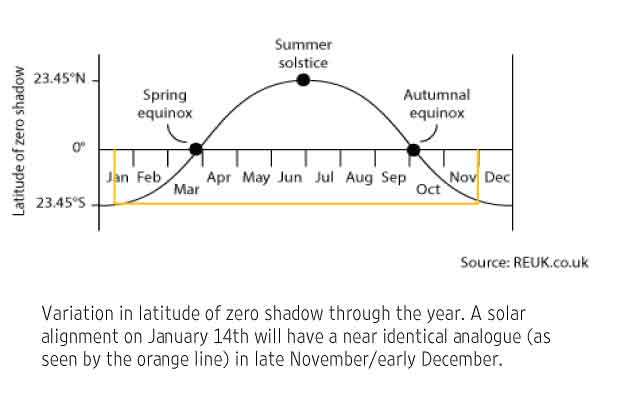

Earlier in this article, we’ve seen that the sun is directly overhead at noon twice a year for every latitude between the tropics (and only once at the tropics—at the solstice). Since the Surya Majjana does not occur on a solstice, and Bengaluru is not on a tropic, it follows that there is another date on the other side of the solstice, when the sun follows a near-identical apparent path across the sky, and aligns perfectly with the idol, like it is at Makara Sankranti.

Hence, the phenomenon of Surya Majjana should be observable on that day too, but this is not publicly known or acknowledged by the temple authorities.

The rays of the sun illuminating all but one sculpture at Abu Simbel. Photo: AFP

The rays of the sun illuminating all but one sculpture at Abu Simbel. Photo: AFP

In order to explore this theme further, I looked for other structures around the world which have a similar, cleverly designed and short-lived solar phenomenon as their main draw. The Abu Simbel rock temples witness a similar event; it is believed that the axis of the temple was positioned by ancient Egyptian architects in a fashion such that on two particular, non-contiguous days at sunrise, the sun would illuminate all the sculptures on the back wall, except for Ptah—the god of the underworld—who always remains in the dark.

There are other temples in India—the Srivaikuntanathan temple at Srivaikutam and others—where similar sights are witnessed, but all of them explicitly publicize two distinct events, unless they occur on a solstice.

My search for similar "paired" solar events took me to another corner of the world. The Anthem Veterans Memorial—located in the Anthem Community Park in Anthem, Arizona—was constructed to honour the service and sacrifice of the US armed forces. The memorial consists of five vertical pillars (with elliptical holes bored in them), which signify the five branches of the US military.

The monument has been designed so as to allow the sun’s rays to pass through five ellipse of the five pillars, and form a perfect spotlight over the mosaic of the Great Seal of the United States, on 11.11am each Veteran’s Day, 11 November.

The rays of the sun passing through ellipses carved in five upright pillars and illuminating the mosaic of the Great Seal of the US at the Anthem Veterans Memorial in Arizona. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The rays of the sun passing through ellipses carved in five upright pillars and illuminating the mosaic of the Great Seal of the US at the Anthem Veterans Memorial in Arizona. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On the memorial’s webpage, chief engineer Jim Martin notes that they used a mean of 100-year-old data in order to create this illumination at 11.11 (with a time fluctuation of ±12 seconds). Once again, this is a phenomenon that should occur twice as the event is not on a solstice. But here too, the website didn’t explicitly mention the second occurrence, or that it was an annual one-off.

I sought out Martin over email. He confirmed my suspicions. There is in fact a second occurrence of the alignment, in January. “In fact many of the pictures that you see floating on the internet were probably taken on the January occurrence since the Veterans Day Ceremony is quite crowded during the illumination. There is a little variance in the date of the return illumination. As you might guess, we do get questions from around the globe about the math and this same question came up a couple years ago”.

To his credit, he shared with me a detailed PDF containing the math of the memorial—which had a descriptive account of the various computations, and the date of the second occurrence (with near-perfect illumination) around 31 January (though not at 11.11). This second date with the sun has no special connotations. Thus, crowds are conspicuous by their near-absence.

Perhaps the experience of a great, convenient narrative taking precedence over a fact is not unique to a single culture.

The sun has left the building

So, when would the second celestial event occur at the Gavi Gangadhareshwara temple?

The December solstice of 2016 was on the 21st; the Surya Majjana was celebrated on 14 January—after a gap of ~24 days. In the Gregorian calendar that we use today, the solstice points are held to a fixed set of dates, and this is continuously corrected over time to retain them as reference. The latitude of zero shadow varies a lot more slowly (~47 degrees in ~183 days) compared to the sun’s angular position (1 degree every 4 minutes), and hence partial illumination can be observed both at the temple and the American memorial on the days neigbhouring the events.

Hence, and we can skip more math here, the corresponding event of a second Surya Majjana with near-identical illumination would have occurred ~24 days before the solstice—around 28 November 2016.

Would it have taken place at a similar time in the day?

The short answer is no. The long answer is: It’s complicated and has to do with the earth’s elliptical orbit around the sun. In the temple’s and the memorial’s cases, though the phenomenon occurred at 5.19pm this year, it occurs within a band of 30-40 minutes. The band of the second Surya Majjana event occurs about 20 minutes earlier—around 5pm, close to the temple’s evening opening hours.

Shortly after figuring this out, Shylaja noticed that the temple always seemed to open late on certain days in late November. “This has happened too many times for it to be a coincidence. A fifteen minute delay in opening the doors usually spells the end of the spectacle in late November. I am tempted to believe that the temple authorities are not keen on associating the event with a second date”.

What about the future? How will these dates move?

Ignoring other long-term celestial effects, Makara Sankranti would continue to “slide” away from the December solstice every ~72 years. In about two centuries, Makara Sankranti will be celebrated on 17 January, one day after the present extent of partial illumination of the Shiva linga. From then on, the festival and the Surya Majjana would continue to diverge slowly for thousands of years (and then converge again later).

Shylaja feels that this is an important part of evidence regarding the recentness of the narrative: “This overlap between the dates of illumination of the Shiva linga and Makara Sankranti is quite transient when compared to astronomical cycles of precession; they couldn’t have done this 150 years ago at the time of Swami Vivekananda, who was born on 12 January, which was Makara Sankranti in 1863. Hence all the circumstantial evidence suggests that the construction of a pillar to move the edge of cave, and shifting the sun’s rays at solstice from illuminating the shrine was quite recent”.

The renovators of the temple didn’t have to use the crutch of a harvest festival in order to draw attention to their brilliant design. The fact that some of the astronomical features of this temple occur only in a handful of places across the world itself is a mark of the collective expertise of its architects all along its history.

The result of Shylaja’s efforts at the Gavi Gangadhareshwara temple was anything but chasing shadows. In 2008 the team published their results in the Current Science journal. It is a paper well worth reading to understand the more technical aspects of this story.

For moment imagine what would have happened if the renovators had constructed the same pillar and window system, but allowed the sun’s rays to bathe the idol only on the day of the solstice rather than the present Makara Sankranti configuration. The window of opportunity to view this beautiful, ephemeral phenomenon would have been unique, and it would have retained its transcendental charm by continuing to occur on the same Gregorian calendar date of uttarayana for posterity. Alas.

The author gratefully acknowledges the various inputs and photographs provided by B.S. Shylaja, Jayanth Vyasanakere and Nagraj Vastarey towards the formulation of this article.

Vyasa Shastry is a materials engineer and a consultant, who aspires to be a polymath in the future. In his spare time, he writes about science, technology, sport and society. He has contributed to The Hindu (thREAD) and Scroll.

Comments are welcome at feedback@livemint.com