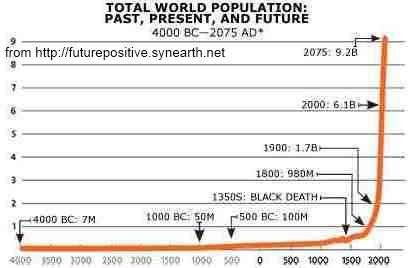

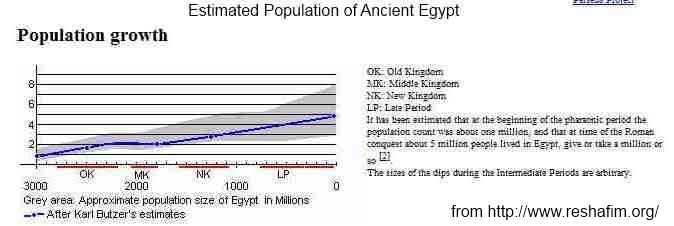

According to the graph on the World Population wiki page, global population at 1000 BC was about 50 million. The vast majority of that would have been in the areas of intensive farming, which at that time means Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and perhaps the Indus valley.

So that number doesn't seem completely out of line. However, Israel is much more marginal agricultural territory than Mesopotamia. Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel, by Paula M. McNutt postulates a far lower population for the area. In particular, based on archeological evidence, perhaps 40,000 people in the 12th century (which gives them a lot of ground to cover to make a over a million warriors in the next 2 centuries). She admits this doesn't jibe well with biblical accounts.

For a modern comparison, the state of Israel today has about only 1.5 million men considered "fit for military service". So this passage would have you believe they almost had as many available in the same area 3000 ago as they could muster today.

Note that current thinking is that Samuel was written sometime around 630-540 BCE, which would have been 300 to 500 years after the events being described. As such, this portion of The Bible should not be taken as a literal history.

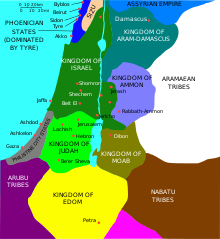

The edit I made to the question (adding back in the bit about Judah) should be your first clue. There was no such thing as "Judah" until the civil war after the death of Solomon in 930 (50 years later). That's when the state split, with the 10 northern tribes continuing to call themselves "Israel" and the two southern ones calling themselves "Judah" (which was one of the two tribes' names).

So the sentence is an anachronisim. There was no such split then, and "Judah" was just one of the 12 tribes in the country. Most likely if such a report were given, it either wouldn't have been split up at all, or it would have been split up by tribe (which would have required 12 numbers, not two).

Samuel was trying to relate a story, and tell some deeper truths about the authors' conception of God. It was not trying to be a modern-style historical documentary. If you are poking around in it looking for history in every detail, you are completely missing the point.